Pulmonary arterial hypertension, or PAH, is a rare, progressive condition that can have a dramatic impact on an individual's ability to work or care for their family. If left untreated, those impacted by PAH can face a wide range of complications. Fortunately, in recent years, research has produced several promising treatments. However, as is so often the case, the existence of a therapy doesn’t mean that it’s accessible to all — or even some — patients.

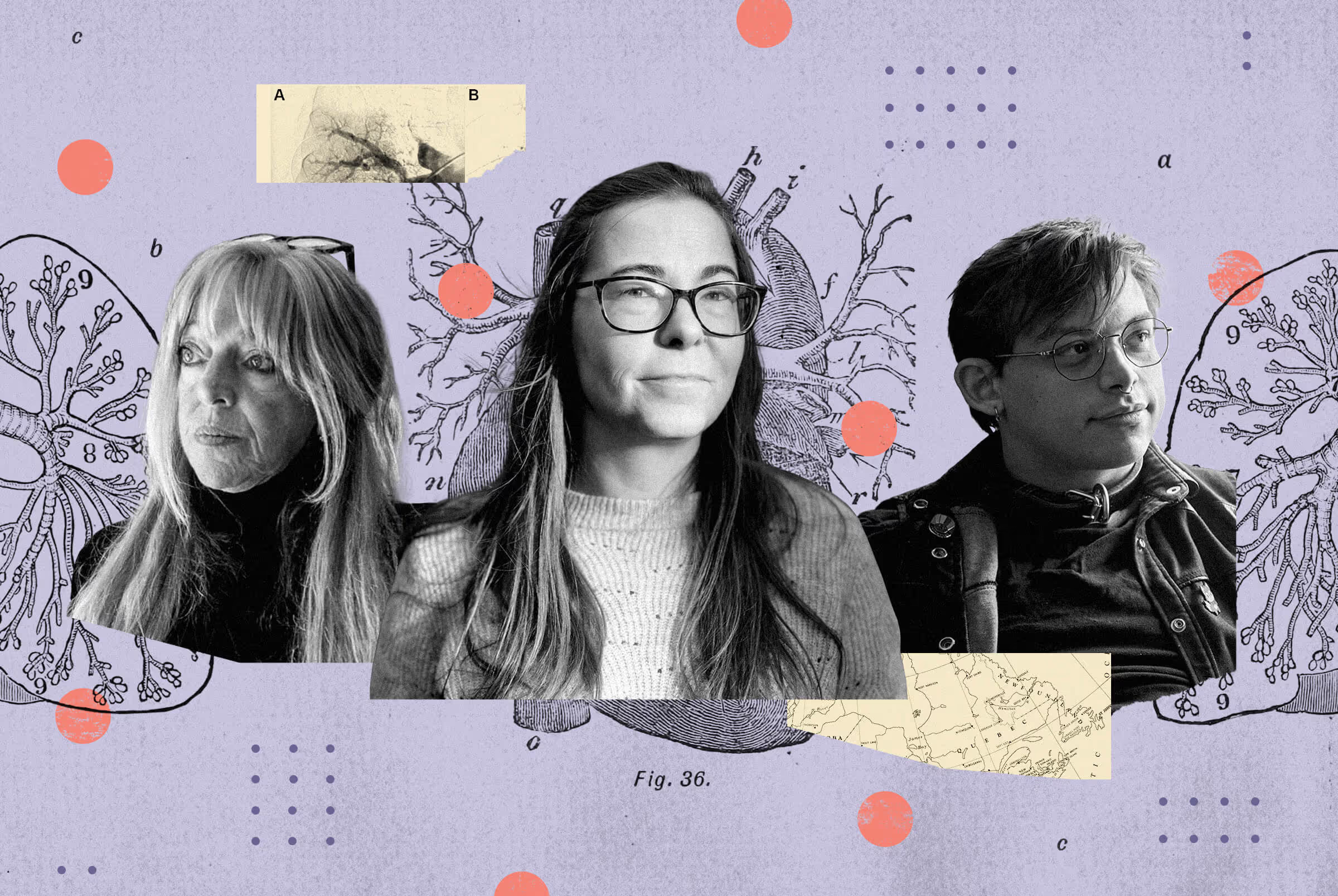

We spoke with Tarya Morel, Rose Jardim, and Angel Ouellet, three Canadians living with PAH, to underscore the precarious nature of their disease and stress the importance of prompt access to innovative rare disease therapies.

Tarya Morel

Looking back, I’ve had difficulties with shortness of breath for as long as I can remember, but it never really occurred to me that it might be a serious medical issue. When I became pregnant, my breathing issues got worse, and they were joined by bouts of dizziness and fatigue. Of course, pregnancy brings with it all sorts of symptoms, so no one thought much of it.

But then my son was born, and none of my symptoms went away. I kept going back to my doctor saying, “I’m not feeling any better” and “This isn’t just new-mom-tired.” I was not okay.

When I finally got diagnosed with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), my family doctor explained the disease, but it was all just white noise to me through the adrenaline. In the end, she looked at me sadly and told me to go home and enjoy my time with my baby. At home, I made the mistake of consulting Dr. Google. The statistics painted a very bleak picture. It looked like I had, at most, one good summer left with my new child. I was crushed; the dreams I had for my future seemed impossible.

That was 12 years ago. I’ve had my ups and downs, but I’m still going strong. I just celebrated my 10th anniversary at work, and I’m thriving. Unfortunately, my marriage didn’t survive my diagnosis and all that came with it, but I’ve since remarried a wonderful man. Together, we’ve created a big, blended family — the family I’d always dreamt of. I’ve lived a whole life I didn’t think I’d get to have.

But the reality is that this is a progressive, incurable disease. So even when you’re stable on a therapy, it’s always in the back of your mind that it might stop working, and that you’ll have to move to another treatment. I’ve been through that. Fortunately for me, science has always stayed a step ahead of my disease, but I’m running out of options.

This is why it’s so frustrating and scary when there are therapies that my community can’t access. I’m in Facebook groups with PAH patients living in the U.S. who are receiving access to therapies that we don’t have in Canada and there are some truly amazing stories of how well they’re doing. I see people posting their test results, showing dramatic improvements to their heart function, and people excited to have cleaned the house without feeling exhausted. I see people going hiking, stunned that they can breathe again. There’s nothing I would love more than to be able to go hiking with my family.

It’s a hard pill to swallow that where I live might determine how long and how well I live, how long I can be productive and contribute to society, and how much time I get to spend with my husband and our children.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare, progressive disorder characterized by high blood pressure (hypertension) in the arteries of the lungs (pulmonary artery). The pulmonary arteries are the blood vessels that carry blood from the right side of the heart through the lungs.

DID YOU KNOW?

Rose Jardim

When I was 50 years old, I cut myself while shaving my legs. And then the cut just didn’t heal. It developed into a deep ulcer that wouldn’t close. And then I got another one. And another.

I’ve worked as a hairstylist my whole life, so I was on my feet all day long. My doctor told me it was probably that plus water retention. So he gave me water pills. For eight years, this continued. I’d get more ulcers, and then my doctor would run a few tests and prescribe me water pills. The pills made me swell up like crazy, so my weight was always going up and down. One week I’d look like the Michelin Man, the next week I’d be wearing a size 10. That’s really hard on the mind.

My niece finally suggested I visit a massage therapist, just to get the blood circulating better in my legs. When I arrived, the masseuse took one look at me and said this wasn’t something they could fix. He sent me to the hospital.

At the ER, I passed out as soon as I walked through the doors. They told me that if I’d waited one more day before coming in, I probably would have died. The water had built up so much, I was drowning in it. It had damaged my heart, my lungs, my kidneys, and my liver. Everything. This is what happens when pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) goes undiagnosed and untreated.

I was told if I didn’t stay off my feet, I was going to lose my legs. I had to stop working, which was unthinkable to me. Being a hairstylist was my livelihood and the heart of my social life. It was my identity. I completely retreated from the world. I stopped wanting to see anyone. I spent a year in constant pain. I became a totally different person. It was an angry, terrible time.

I missed so much. I wasn’t cutting hair. I wasn’t seeing my old friends. I wasn’t meeting new people. My first grandchild had been born just before my diagnosis and I basically missed the whole first year of her life. I couldn’t be even a fraction of the grandma I’d wanted to be.

For PAH patients, the difference between one therapy and another can be night and day. And how a therapy is taken can also have a big impact on your life. I had to wear a pantsuit to my younger daughter’s wedding because the gown I would have preferred interfered with the device that administers my medication. All of that aside, things have been OK. But what pushes me forward is the hope that one day — sooner rather than later — things will get better. And, hopefully, when my granddaughter gets married one day, I’ll be able to pick a gown.

PAH can significantly impact a patient’s ability to find and keep a job. For younger patients at the start or middle of their careers, PAH can also negatively impact their career advancement, preventing them from earning higher incomes.

DID YOU KNOW?

Angel Ouellet

One day when I was six years old, I saw a favourite teacher at the end of the corridor at school and ran to give them a hug. Afterwards, the teacher called my mother and told her to take me to the hospital. When I’d hugged them, they’d felt my heart beating out of my chest.

Growing up after that, I understood I had a medical condition, but I had no idea how serious it was. I remember at one point my doctor gave me a book about pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), so I’d be able to better understand it. I just put that book on my shelf. Then, years later, I randomly pulled it down and started flipping through it. I landed on a section about life expectancy after diagnosis. Some quick math told me I should have died four years earlier.

Through my whole childhood, my mother and grandmother — my whole family, really — had been so supportive of me. They’d always tried to give me whatever I wanted, within reason and within our limited financial means. I’d had no idea that the doctors had told them I likely wouldn’t make it to my teenage years.

I’m 28 now and I’m still here. I’ve found my communities full of those who are also a little different. I have a rewarding career in cybersecurity and a loving partner. PAH has shaped every aspect of who I am, and I think it has made me a better and more empathetic person.

I work a reduced schedule because of my health. I also need to ask for certain accommodations, which always feels a bit precarious in today’s job market. I don’t have the kind of fallback options other people have. I can’t work in a restaurant or a factory because my body just couldn’t handle it.

Everything’s just that little bit harder. That includes getting out of bed in the morning, going up and down a set of stairs, or commuting to work on the other side of Montreal’s Mont Royal. That’s why I’ve started using an electric skateboard, which I call my mobility scooter. All of that said, of all the people I’ve met with PAH, my story is one of the easiest. But that could change any day.

I don’t spend much time worrying about how my disease might progress, but the truth is that — ever since I flipped open that book — I’ve approached life as though I had an expiry date. My disease is well-controlled right now, but I know how quickly things can change. It’s scary to be in this situation, knowing that rare disease communities often face so many barriers to accessing innovative therapies. That’s why I advocate. For my future self but also for those who need access today.

PHA Canada is a federally registered charity established in 2008 by patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals to work together to better the lives of Canadians affected by pulmonary hypertension and represent a united national PH community. To learn more, click here.

Made possible with the financial support of Merck Canada.

%20(1).jpg)