“I spent October of 2018 surfing in California and laying the groundwork for a winter business there to complement the successful summer paddleboard business I had here in Canada. Life was good.

Then, on November 6th, 10 days after I returned from California, I started feeling sick. It began with an earache, but then the pain expanded and compounded. I went to a walk-in clinic initially and they diagnosed me with an ear infection from the ocean water. I was prescribed antibiotics and sent home, but the pain only got worse. It was excruciating.

Over the next week, my symptoms quickly progressed. Fatigue, vertigo, vomiting, and pain that was so bad I couldn’t think or sleep. On November 11th, I woke up in the upstairs spare room at my mother’s place and I knew something was different as soon as my feet touched the floor.

I struggled so hard to get down that single flight of stairs. When I reached the bottom, I called out to my mother for help. When she saw me, she got this strange look on her face and then told me not to panic. She helped me hobble over to a mirror and there I saw that the right side of my face had collapsed. I looked like I’d had a stroke.

I’d already been to two different hospitals that week. At the third I was finally given the diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome, a rare neurological condition brought on by the reactivation of the shingles virus, the same virus that causes chickenpox. They told me that cases of Ramsay Hunt can range from mild to very severe, and unfortunately I’d landed at the severe end of the spectrum.

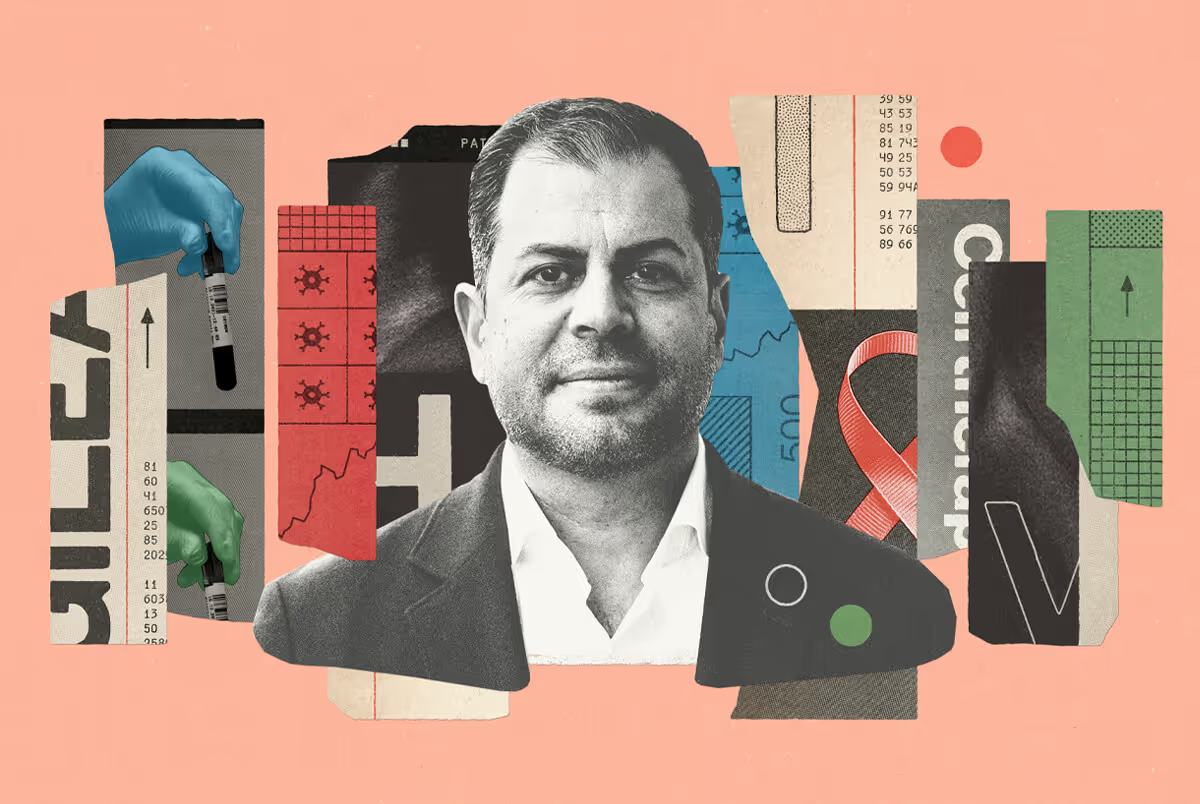

I was 35 years old, an athlete, an entrepreneur. And I lost it all to this disease. I lost my mobility, my business, my independence, my social life. I lost my whole identity. And I was told I couldn’t reasonably expect to ever get any of it back. This was the moment of ultimate hopelessness.

In that moment, it was impossible for me to imagine better days. Today, six years later, so many better days have come, but I still clearly remember those depths of despair. There’s no way out of that pit without support and guidance, and I think every day of those who are still down there.

Before I developed Ramsay Hunt syndrome, I lived my life on the water. I owned and operated a paddleboarding business that let me share my love of the sport with others. I was young and it felt like everything was possible. But over the course of a week, my life changed forever.

Ramsay Hunt left me with hearing and vision loss, chronic vertigo and brain fog, and the right side of my face paralyzed. It left me barely able to walk across a room, let alone spend long days on the water. I was told, quite bluntly, that I’d never paddleboard again.

I was without hope, and the walls started going up. I began to isolate myself from everyone who cared about me. I needed full-time care, and I felt so much guilt and shame over the fact that, despite everything that was being done for me, it still wasn’t enough. I came coldly to the decision that the best outcome for me, and for those I loved, was simply for me to no longer exist. And so I tried to take my own life.

“One person in five in this country struggles with their mental health, and up to 12 die by suicide each day. I don’t want anyone else to ever struggle as I struggled.”

It was only on the other side of that, while staying at a mental health crisis centre, that I realized how much what I was going through was a matter of mental health as well as physical. For five months afterwards, I met a counsellor for coffee at the Tim Horton’s near my house once a week. And those conversations, combined with just getting out of the house, changed everything. At first I was taking an Uber to meet her, but soon I was feeling bold enough to challenge myself to walk, even though I knew just those few blocks were going to knock me on my ass.

When you’re trying to lift yourself out of the darkness, finding that first challenge, however small, that you can actually overcome builds confidence. And, with support and encouragement, that little sense of accomplishment can grow into the greater confidence to take on bigger challenges.

Mental health challenges are so widespread. One person in five in this country struggles with their mental health, and up to 12 die by suicide each day. I don’t want anyone else to ever struggle as I struggled. But it’s hard to know where to even begin.

I chose to begin by talking openly about my own experience.

By August of 2019, I was paddleboarding again. I’d been off the water for a long time since Ramsay Hunt syndrome left me with disability and mental health challenges so severe that I tried to take my own life.

My first time out, I lasted three minutes before the dizziness and nausea were too much. It took me a whole day to recover from those three minutes. But the next week I managed five minutes. I learned persistence.

Around this time, a friend suggested that my story could help others, so I signed up for an inspirational speaking competition. I didn’t realize at the time, but it was actually North America’s largest. Many of the entrants were published authors, had huge followings, had given TED talks. For me, it was my very first time speaking publicly. And I won. My talk went viral, got millions of views, and everything just built up from there.

I started hosting events, using my new platform to raise awareness and advocate for mental health. Then COVID happened, and I needed to find a way to reach people even as they isolated. I got the idea of crossing the Great Lakes on my paddleboard as a public testament to what could be accomplished by people with disabilities and mental health challenges. In 2021, I set out to cross Lake Ontario. I only made it halfway, but that failed attempt only strengthened my resolve.

In 2022, one by one, the lakes fell one by one. It was an incredible experience made possible by an incredible team. There were many times when I wanted to give up. I’d be on the water for 30 hours at a stretch, battling vertigo, fatigue, and weather that would change four or five times in the course of a single crossing. No one with a disability had ever done this before. But by taking it one lake, one challenge, at a time, my team and I were able to push through. We raised a lot of money for youth mental health programs, were commended in the provincial and federal legislatures, and were recognized by Prime Minister Trudeau.

I hope this will lead to further support for those with mental health challenges and a broadened awareness of what’s possible for people with disabilities."

%20(1).jpg)